Pugnacity, Power, Prurience and Greed: Preachers from the Frontier to the Television

In the Southern frontier the camp meeting played an unparalleled social role, acting as not only a stricture on other forms of social entertainment such as drinking, horseracing and brawling, but also as an entertaining, revitalizing form of social interaction. While intentions were typically high and holy in the establishment of camp meetings, they often devolved into less than righteous gatherings. The unsupervised, disorderly emotion that frequently characterized the camp meetings soon became their defining characteristic. This mingling of the holy and the unrighteous elements in the religious gatherings of frontier camp meetings similarly has come to define the modern popular religious arena. The modern evangelical movement has frequently taken on the political and monetary motives that it, on the surface, rejects, falling prey to the lure of glamorized, televised popular morality. The frontier camp meeting and the modern evangelical revival meeting are depicted in both historical narratives and literary works as strangely schizophrenic. They meld and blend righteousness and impiety, creating a religious carnival. This incorporation of disparate elements is most clearly exemplified through the almost archetypal characters usually present at both camp meetings and evangelical revivals. Among characters such as the trickster and the virgin, one character stands out, perhaps surprisingly, as one of the most important and engaging players in the camp meeting and evangelical arenas in both fictional and historical accounts: the preacher. Embodying a strange duality, the camp meeting preacher is at one time depicted as pious and revered and simultaneously bawdy, lustful, and uneducated. Similarly, the popular modern understanding of the evangelist preacher imagines him as deceitful under a sheen or virtue. It is clear through the study of these accounts that embodied within both preachers are elements of brazenness and impudence, holiness and righteousness, which meld to form a unique historical and literary figure. As the dual nature of the camp meeting preacher has evolved throughout American history, the modern day evangelist preacher, known for his dramatic antics, fundraising events, and glitzy, theatrical services has emerged; in both preachers there is an element of both piety and trickery, emerging from the fertile soil of life on the frontier and Hollywood style.

The Camp Meeting and its Preachers

The Camp Meeting and its Social Function

The frontier camp meeting not only served a particular religious purpose, namely, bringing unsaved souls to faith, it also acted both inside and outside the social constructs of its day in very particular ways. The frontier was governed in many ways by its social constructs that separated men from women, whites from blacks, rich from poor. It was an extremely hierarchical society in which one's worth was based on one's societal position. Unlike in more urban areas, where the social hierarchy was fairly predetermined by one's parents, the frontier hierarchy was, perhaps, more fluid. One gained stature through one's ability to live and thrive within the bawdy, dangerous frontier world. However, there was a particular structure that was adhered to by most without question that separated and classified people according to various standards. The camp meeting often challenged this hierarchy. In his essay, "Reminiscences of a Camp Meeting" Reverend W.I. Ellsworth speaks of the power the camp meeting held to erase social class and gender distinctions. He writes, "What a scene to gaze upon! There was bowed the sire and the son, the man of wealth and the man of penury, the dweller in the city and the dweller in the country, side by side, seeking the same Savior" (342). The camp meeting offered an alternate social structure from the hierarchical class system to which the frontier normally adhered. Nathan O. Hatch writes that those who supported the camp meeting movement, ". . .began to piece together a popular theology that inverted the traditional assumption that truth was more likely to be found at the upper rather than the lower reaches of society. This perspective sprang from an intensely egalitarian reading of the New Testament" (45). Therefore, while those who were disenfranchised and lacking in power often identified and appreciated the camp meetings leveling power, the same meetings were often viewed as dangerous and threatening to those at the top of the social totem pole.

Not

only did the camp meetings challenge social hierarchies, but they also offered

new social activities outside of the normal routines of daily frontier life.

In And They All Sang Hallelujah: Plain-Folk Camp-Meeting Religion, 1800-1845, Dickson Bruce notes the important role that the camp

meeting played in the life of the frontier society, writing, "The frontier

world was a difficult one, and no doubt drinking, gambling, and brawling all

provided a temporary escape for the frontier folk. . . The camp-meeting made

for a similarly intense and exciting experience for its participants" (130).

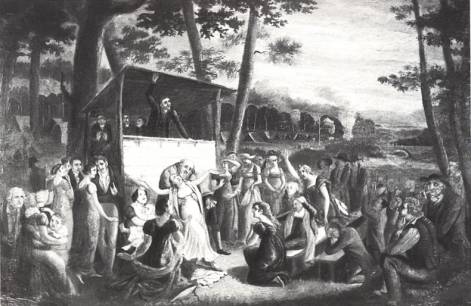

Illustrations of camp-meetings portray the camp-meeting as a social event, in

which attendees could break free from the otherwise strict societal expectation.

In what were called 'exercises,' congregants were often brought to the point

of hysteria by the preacher's exhortations. Again, these activities had a leveling

effect on the social structures of the frontier. Unlike the more raucous and

violent pastimes of the men in frontier society, the camp meeting experience

was one in which women, children, and men could all take part equally.

Not

only did the camp meetings challenge social hierarchies, but they also offered

new social activities outside of the normal routines of daily frontier life.

In And They All Sang Hallelujah: Plain-Folk Camp-Meeting Religion, 1800-1845, Dickson Bruce notes the important role that the camp

meeting played in the life of the frontier society, writing, "The frontier

world was a difficult one, and no doubt drinking, gambling, and brawling all

provided a temporary escape for the frontier folk. . . The camp-meeting made

for a similarly intense and exciting experience for its participants" (130).

Illustrations of camp-meetings portray the camp-meeting as a social event, in

which attendees could break free from the otherwise strict societal expectation.

In what were called 'exercises,' congregants were often brought to the point

of hysteria by the preacher's exhortations. Again, these activities had a leveling

effect on the social structures of the frontier. Unlike the more raucous and

violent pastimes of the men in frontier society, the camp meeting experience

was one in which women, children, and men could all take part equally.

The Camp Meeting Preacher

However, because this religious experience was in direct opposition to the other secular social activities, camp meetings and the preachers who espoused the camp meeting ideals often came under attack by some of the people on the frontier. Because the camp meeting preachers often spoke against the more secular forms of entertainment such as brawling and drinking, they caused quite a backlash from some frontiersmen who were quite happy with their social standing and their rough way of life that solidified their hold on power. In her book Southern Cross Christine L. Heyrman speaks of the ways in which preachers were viewed as threats to the Southern frontier social order, writing, "[a]t stake for all masters was maintaining their independence, the essence of masculine honor, and when they felt it had been violated, the carapace of their seeming civility toward the clergy cracked" (216). Camp meeting preachers represented, for these frontiersmen, an emasculating force that wished to rob them of their independence by destroying the more bawdy social orders and converting them. This negative view of camp meetings and camp meeting preachers often created quite a dichotomy between negative social perception and the reality of the camp meeting preachers' positive intentions. Despite varied backgrounds and styles, many of the religious leaders that took part in camp meetings were committed to their calling and morally grounded in Scripture. There are wide-ranging accounts of the sacrifices that many preachers and circuit riders made in order to witness to the people living on the frontier. For example, in the Marian Douglas poem "Before the Wedding" she writes:But when camp-meeting came around. . .He told the Gospel story/So thrillingly, through all the grove/Went up one shout of 'Glory!'/Rough men were bowed, hard sinners wept/I owned his power to hold me. . .'A Methodist itinerant,/Who keeps forever moving,/Moving, moving moving,/Just two years in a place./That's too hard a way,' thought I/ 'To run the Christian race!'" (Douglas, 685)

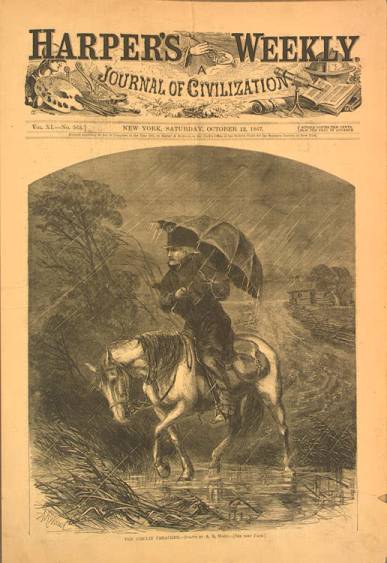

The

life of the frontier preacher was not an easy one. Not only were many of them

constantly on the move, as Douglas notes, but they often had to deal with

inclement weather and rowdy hecklers. An image from the cover of Harper's

Weekly illustrates what some saw as the unflagging endurance and commitment

of the itinerant preachers (shown at left). The image depicts the wind- and

rain-beaten preacher as he moves steadily forward in order to do his duty

to God and his congregation. However, the trials that these preachers faced

were not without reward. In many cases camp meeting ministers were highly

esteemed by their congregations and the communities in which they worked,

making them some of the most widely revered men on the frontier.

The

life of the frontier preacher was not an easy one. Not only were many of them

constantly on the move, as Douglas notes, but they often had to deal with

inclement weather and rowdy hecklers. An image from the cover of Harper's

Weekly illustrates what some saw as the unflagging endurance and commitment

of the itinerant preachers (shown at left). The image depicts the wind- and

rain-beaten preacher as he moves steadily forward in order to do his duty

to God and his congregation. However, the trials that these preachers faced

were not without reward. In many cases camp meeting ministers were highly

esteemed by their congregations and the communities in which they worked,

making them some of the most widely revered men on the frontier.

Deceitfulness and Trickery

However, despite the reverence they received from some members of frontier society, the voice of the powerful and the threatened often drowned out these positive views. Whether they were honest or not, camp meeting preachers were often depicted by frontiersmen as deceitful con men who carried ulterior motives in their camp meeting sermons and exercises. Literarily, camp meeting preachers were often pitted against renowned tricksters and were constantly proven more deceitful and impious than those who were blatantly irreverent. In George Washington Harris' "Parson John Bullen's Lizards" the preacher at the camp meeting is portrayed as a gluttonous man who is far from righteous. Sut Lovingood, the humorous trickster protagonist, describes him as, "The durnd infunel, hiperkritikal, pot-bellied, scaley-hided, whisky-wastin, stinkin ole groun'-hog" (208). Hyperbolic or not, Sut's description of the camp meeting preacher illustrates the ways in which camp meeting preachers were regarded as dangerous to the social norms. Constantly, literary tricksters attempt to prove the camp meeting preacher as unworthy of any social reverence. By showing them to be men that were no better than a mere huckster, they pointed out the community's mistake in holding the preachers in high regard. In Johnson Jones Hooper's "The Captain Attends a Camp-Meeting" the trickster Simon Suggs is easily able to convince the congregation that he wants to become a minister, clearly illustrating the willingness of the camp meeting audience to follow a leader, regardless of whether he was righteous or not. Through these literary works, the piety and the religious role of the camp meeting preacher is constantly called into question as the authors point out the ways in which these ministers are merely attempting to upend the social structure in order to gain power and influence for themselves, while stealing it from the "real men" of the frontier.Sex and Violence

Camp meeting preachers were not only subject to literary satire, but historically their intentions and religious roles were also constantly under scrutiny. It is clear that some of the literary satire was well warranted. While preachers often spoke against social rituals such as brawling and sex, hypocritically they also often took part in them. Obviously camp meeting ministers utilized various methods of preaching and witnessing, among them some that were overtly violent and others that carried explicitly sexual overtones. Frequently, because of these methods, the frontiersman's negative view of the camp meeting preacher was actually confirmed and justified.

Caught up in religious fervor, preachers would sometimes resort to coarser methods of 'bringing people to Christ,' at times bullying them into conversion. Additionally, if they felt threatened by present troublemakers, camp meeting preachers were unafraid of resorting to extreme violence. Heyrman notes, ". . .preachers sought respect among masters less by calling on religious charisma—which was, after all, the sole resort of white women, youths, and blacks—than by claiming the combative skills prized by most southern men" (236). It would seem that camp meeting preachers were aware of their stereotypically emasculating role. Some actively rebelled against it by adopting, or reverting back, to the normal and accepted violence of the frontiersman. These aggressive techniques were not only a means of survival, but also a way of gaining respect from their fellow southern males. Often this violence was used in order to control congregations, but it was also merely used as a reminder of the minister's position of power. Heyrman recounts the story of the Tennessee preacher John Brooks who, "overhearing one 'noted infidel. . .disparage Jesus Christ as a d—d bastard. . .threw him into a large fire and put my right foot on him to hold him there'" (237). The social structure had been revised by the camp meeting preacher in order to place the minister in a role of power. The same preachers who had created an atmosphere of social equality often felt the need to then maintain the power that they had perhaps inadvertently been warranted through the reverence of their congregants.Although many ministers utilized muscle to overcome those who opposed their preaching, Reverend Peter Cartwright is one of the most renowned. Once, when some rowdy men threatened to distract his congregation with their boisterous exclamations, Cartwright reportedly, "warned the man that if he did not remain quiet he would pound in his chest. . .The mob leader swung wildly at the fighting preacher but missed him. Cartwright saw an opening, hit the leader on the burr of his ear, and knocked him down. . .in a few minutes order was restored" (Mondy, 204). These exercises in violence, and others like them, helped establish the preachers as equals among the Southern male laity that they served. Still, while it kept their congregations under control, it certainly undermined their claim as peaceful men of God, and also undercut their message of social equality.

In addition to occasionally utilizing violent means in order to spread the Gospel, camp meeting preachers were also in danger of succumbing to the weaknesses of the flesh. Sometimes, utilizing their position of esteem, the preachers would play out lustful fantasies among the women that they hid under the guise of 'religious exercises.' It was not uncommon for "[p]rostitutes [to troll] the outskirts of encampments, soliciting business from both the backslid and the devotedly hearten. . ." (Heyrman, 231). However, for ministers at camp meetings the religiously devout women were much easier targets for lustful practices. In "A Story of the Camp-Meeting" Mary E. Grafton writes of the camp meeting preacher, "he had been in neighborhoods where Dobson, years ago, before he became sanctified—was well known as a 'revivalist,' and he knew his reputation was such that 'family men' looked well to the ways of their own households, in the particular districts in which he happened to be 'evangelizing'" (501). Exploiting the power a minister had as a community leader, some preachers took full advantage of the esteem of religious women. In Johnson Jones Hooper's "The Captain Attends a Camp-Meeting" one of the preachers is portrayed as an underhanded, lustful character. Hooper's protagonist and narrator Simon Suggs observes a camp meeting, noting of one of the leaders, ". . .ther he's been this half-hour, a-figurin amongst tem galls, and's never said the fust word to nobody else. Wonder what's the reason these here preachers never hugs up the old, ugly women? Never seed one do it in my life—the sperrit never moves 'em that way!'"(Hooper, 293). While there are fewer accounts of preachers actually taking sexual advantage of a member of his congregation, there are many implications of unnecessarily sexual activities initiated by the ministers and directed toward young women in the congregation, not only in Hooper, but also in Harris and Mark Twain.

A Shifting Theology

The power that camp meeting preachers had over their congregants was demonstrated through their effective use of violence and sex in order to win converts. However, it is through sermons that preachers most clearly lay out their egalitarian theology that allows uneducated preachers who are on par socially with the disenfranchised members of society to claim and hold on to social power and influence as purveyors of religious 'truth.' Anne C. Loveland, in her book Southern Evangelicals and the Social Order: 1800-1860, states, "For southern ministers, as for virtually all nineteenth century evangelicals, preaching was the most important duty" (38). The camp meeting sermon was a special event. As Harris' Sut Lovingood describes them, these sermons were "pow'fly mixed wif brimstone, an' trim'd wif blue flames" (208). Often it was because these preachers were uneducated men who were part of the 'plain-folk' as much as their congregation that they were able to speak to their audiences clearly and emotionally. The camp meeting preacher insisted that theology would not often get in the way of the message of Scripture. John B. Boles in The Great Revival: Beginnings of the Bible Belt writes, "[a]s the revival spread across the upper region of South Carolina, it became obvious that the camp meeting thrived best under the tutelage of the less-educated, more emotional [preachers]" (95). This emphasis on manipulating the emotions rather than speaking to one's intelligence caused the camp meeting ministers to pit themselves, fairly intentionally, against the theological establishment of the day that favored order, class systems, and strict liturgy. The camp meeting preachers authored a new method of reading the Bible that allowed any believer equal access to Scripture. They believed that theological education was unnecessary to understanding Scripture. In fact, they argued, it often became a stumbling block for believers. The camp meeting sermon, therefore, emphasized egalitarian theology and the necessary emotional response to faith.

As the main vehicles of conversion, sermons were understood to convey the untempered truth of the Gospel. In "Going to a Camp Meeting" by a Mrs. H.C. Gardner, the writer illustrates the way in which a well-delivered sermon could solidify a preacher's reputation and garner him praise and reverence from all who heard it. She writes:

I can not yet convince myself that the sermons to which I have listened at camp meeting do not surpass in many respects, in unction and power, for instance, all other sermons that I have heard. . .If there is any thing like eloquence in [the preacher] it is sure to be aroused. Then there is a fervency of spirit, a melting love and concern for the impenitent, which is seldom exhibited so prominently elsewhere. (Gardner, 646-647)

"Even those previously unmoved by the emotion of a camp meeting could be swayed, Gardner implies, by the power of a sermon's delivery. It was the emotion behind a sermon more than any eloquence of intellectual power of the preacher that moved the camp meeting audience. Reverend Gustavus Hines writes in his essay "The Camp Meeting: A Reminiscence," ". . .there was no daubing with untempered mortar, no mincing the truth of God's word, no effort to preach a splendid sermon, no attempts to lower the standard of the Gospel truth to accommodate the whims and prejudices of the fastidious. . ." (259). The camp meeting sermon intended to deliver the power and truth of Scripture without any nuance or theological shading. According to some, it was actually because of the preacher's lack of education that he was able to tap the true core of religious emotion through what was seen as his truthful, unfettered reading of Scripture, and his unbiased condemnation of sin.

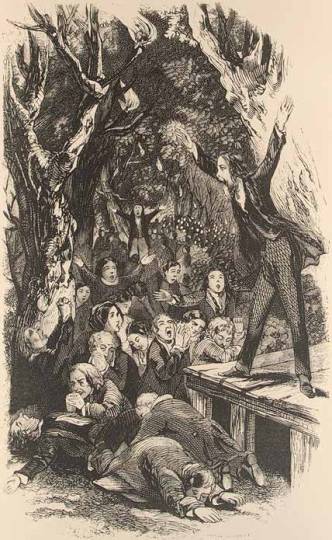

While

sermons were meant to bring listeners to an emotional feverpitch in order that

they might convert, often they failed to illustrate the unfettered Gospel, instead

illustrating merely the hypocritical bravado for which the camp meeting preachers

were often criticized. The sermons often ignited an immediate reaction from

the congregants as the ministers physically threw themselves into their sermons,

kindling passions within the congregation that were unrivalled by most accounts

. However, these 'hard-shell,' theologically conservative sermons also provided

ready fodder for a number of humorists.

While

sermons were meant to bring listeners to an emotional feverpitch in order that

they might convert, often they failed to illustrate the unfettered Gospel, instead

illustrating merely the hypocritical bravado for which the camp meeting preachers

were often criticized. The sermons often ignited an immediate reaction from

the congregants as the ministers physically threw themselves into their sermons,

kindling passions within the congregation that were unrivalled by most accounts

. However, these 'hard-shell,' theologically conservative sermons also provided

ready fodder for a number of humorists.

Hardin E. Taliaferro's "Parson Squint: By Skitt, Who Has Seen Him" illustrates the coarseness that often identified and defined a camp meeting sermon. While satirical in content, Taliaferro's satirical parody of a sermon does allow for a strange sympathy and, according to Cohen and Dillingham, "it would be more accurate to term his comic sermons recollections or reconstructions rather than burlesques, for in form and language he is faithful to his originals" (129). In "Parson Squint" Taliaferro is able to articulate the manner by which preachers used Biblical texts as confirmation of their own religious views rather than reading them objectively and then interpreting them. Parson Squint uses a passage from the book of Hosea in order to criticize other forms of Baptists, condemning them through the text in an emotional but intellectually unconvincing reading. Getting carried away with tangential subjects, Parson Squint also addresses theological issues and Christian dogma, stretching the text to its limits in order to use it to explain the varying beliefs of different denominations. Throughout the sermon Squint illustrates his lack of formal education. Finally, in a touch of irony Parson Squint states, ". . .the whole wourld, all say we are few and ignunt. Let um say it, ole Squint is able to bear it. . .We kin soon be multipled like the widder's meal and ile, ah! Accordin to the prophesy's o' the prophets, thar's a glorious futer for [us]" (Taliaferro, 147). For Taliaferro the preacher is not particularly harmful, or, perhaps, even hypocritical, although he does harshly condemn other Christian denominations. Rather, he is a victim of his own lack of education and his uninformed pride. The sermon rarely utilizes the text beyond a reading that merely solidifies the preacher's preconceived and preconstructed point.

The anonymously penned "The Harp of a Thousand Strings: A Hard-Shell Baptist Sermon" emphasizes the preacher's lack of education. However, for this preacher, this is a matter of pride, for it is something that he has overcome. He states, "I may say to you my brethring, that I am not an edicated mane in the State of Indianny, whar I live, thar's no man as gets bigger congregations nor what I glisten' although I'm capting of the flatboat that lies at your landing, I'm not proud, my brethring" (Whitehead and Muhrer, 56-57). Once again, the preacher is less concerned with the souls of his congregation than with the advancement of his own career. As a flatboatman, the preacher has already gained the respect of frontiersmen because of the bravery and assumed manliness that that career demands. Not quite as pious as his conservative religious views would support, he continues:

Now thar's a great many kinds of sperits in the world—in the fuss place, thar's the sperits as some folks call ghosts, and thar's the sperits uv turpentine, and thar's the sperits as some folks call liquor, an' I've got a good an artikel of them kind of sperits on my flatboat as ever was fotch down the Mississippi River. . .(57)

The author of the parody implies that the preachers are never as pious as they would like to appear to their congregations. The minister not only owns liquor and other worldly possessions, he is also proud of them. Parodies such as "Parson Squint" and "The Harp of a Thousand Strings" depict camp meeting preachers as being as proud and worldly as their congregants. Hypocritically they condemned other Christians, while they remained revered men of God who, through bootlegging and other presumably impious practices, became wealthy men.

The camp meeting preacher, therefore, is a study in paradox. He, and the camp meeting system in which he worked, continually challenged the existing structures of social authority and class. The preacher insisted that any and all can come to equal understandings of God and faith through simple encounters with Scripture. However, just as he attempted to upend the social hierarchies that existed on the frontier, he continually tried to maintain the power and reverence that he had gained through this social leveling. He was therefore satirized as hypocritical and dishonest by those whose power and masculinity had been challenged, for while the preacher condemned widespread social customs, he also was required to enter and exist within them in order to maintain his social power. This strange balancing act left the camp meeting preacher at once both revered and reviled by those on the frontier and by those religious leaders outside the frontier world.

The Modern Evangelist

The New Movement

The duality between honesty and perversity that existed within the brazen frontier preacher was only the beginning of a longer-lasting tradition of evangelical ministers. Throughout the years preachers have not only been revered as 'God's witnesses,' but have also been feared by those whose social power and standing are threatened by the power of the preacher. It seems there is an indefinite line that exists between divine and the devil in popular imagination, especially when it comes to ministers who exists in the public limelight. This may be most evident in the more fundamentalist preachers who thrive on publicity and television popularity. The resurgence of huge, publicized revivals, and the emergence of televangelism creates a type of preacher whose message is extremely dualistic. While claiming to be preaching the Gospel, these preachers are driven by money, power, and politics. Both revered by their peers and rejected by outside observers, these preachers exist as the modern form of the frontier preacher.

Greed

Unlike the frontier preacher, the modern evangelist is driven less by an upending of social hierarchies than the entrance into such a hierarchy, and the need to climb the hierarchies ladder through the attainment of wealth. Whether as a televangelist or a modern revivalist, it seems that the issue at stake for many modern evangelists is money. Despite the best intentions at the beginning of one's career, often the lure of wealth seems to supplant any of the modern evangelists' former goals. For instance, A.A. Adams, a self-pronounced spiritual and physical healer, became obsessed with money to the point that his previously egalitarian theology shifted in order to account for his wealth. James Morris writes of Adams' youth, "He had started smoking at the age of six, had his first woman at the age of twelve, and at eighteen lived with a common-law wife. By the time he was twenty-three he claimed the reputation of worst sinner in that section of Missouri. . ." (6-7). However, just as sometimes the frontier's tricksters were converted at the camp-meetings, Missouri's sinner, Adams, converted at a Methodist tent revival, and soon joined a Pentecostal Church nearby. While in his humble beginnings Adams was decidedly opposed to the wealth of a minister, after barely making it for a time, his views changed. Morris writes, "At the start of his ministry, he firmly believed that a preacher should not talk about money, that a minister with two suits was a sinner, a pastor with a new automobile, an obvious hypocrite. But living on the edge of poverty had tempered those beliefs somewhat" (9-10). As his ministry grew, Adams observed the huge crowds attending faith healers such as Oral Roberts' revivals. Claiming to have heard a call from the Lord, Adams subsequently entered into the realm of healer also. Soon he was being revered as one of the most influential revivalists of his day.

As Allen's popularity grew, so did the number of critics. The one criticism that Adams could not escape was that he was growing rich off of his congregants, some of whom were poverty-ridden or destitute. Morris writes:

Time magazine decided in its March 7, 1969, issue that his [Allen's] faith healing ministry had for all practical purposes become another sect, and reported, with eyebrows suitably raised, that in the previous year A.A. Allen Revivals, Inc., had grossed $2,692,342—not including the salaries of Allen and his two associate preachers, whose ‘cut,' according to Time, was taken in the form of 'love offerings' from their field campaigns. (5)

As his wealth increased, Adams' theology again slowly shifted. While he himself had been poverty-ridden in his previous life, Adams began to exploit the poor as a faith healer. He encouraged his poor followers to pledge money; if they were faithful, the Lord would help them pay. Morris notes that by 1968 Adams had "refined his peculiar money doctrine into a perverted form of hyper-Calvinism which taught that wealth was a sign of God's blessing. He could not abide followers who remained poor, for that was certain evidence they were out of God's will" (45). Adams remained adamant until his death from alcoholism that his congregants continue to pay him large sums of money. Adams, like other evangelists, had felt the lure of money to be made. Based on the trust of his congregants, who revered him as a man of God, Adams was able to build an evangelical empire.

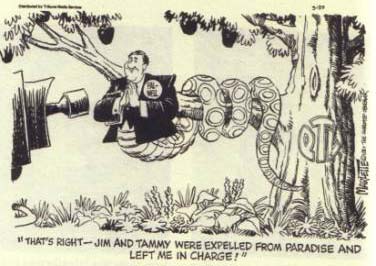

While Adams was only criticized for his excessive

pleas for money, Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker were forced out of the ministry

after it was revealed that they had been not only soliciting money from their

followers, but also misusing the donations. Their huge evangelical empire

was centered in an amusement park called Heritage USA and a television network

called PTL (an acronym standing for People That Love or Praise The Lord, interchangeably).

The empire, built during an American economic upswing, subsisted largely on

donations given by viewers and followers of the Bakkers' ministry. Larry Martz

and Ginny Carroll speak of the Bakkers' pleas for donations, stating, "Giving

to God, of course, meant giving to PTL, and Jim learned to take advantage

of his flock's new prosperities backbone of his [Bakker's] empire was the

mailing list of 507,000 'PTL partners' who were regular correspondents, and

about half of them were pledged to make a monthly contribution of $15 or more"

(10-11). These contributions were supposedly marked for use in the upkeep

of the network and the ministry. However, after credit card companies traced

the spending of both Jim and Tammy Faye, the suspicions mounted. One man who

worked for the Bakkers reported, "On one road trip. . .he [the employee]

was sent out to buy a hundred dollars worth of cinnamon buns, not because

anyone was hungry but because Tammy liked the way they made the hotel room

smell" (Ma rtz

and Carroll, 17). Yet these excesses were only minimal in the larger scheme

of spending.

rtz

and Carroll, 17). Yet these excesses were only minimal in the larger scheme

of spending.

After being investigated by both the FCC and the IRS, it was reported that ". . .the top officials of PTL had been paid $14.9 million more than their services were worth in the years 1981-1987. Of that, Jim and Tammy had taken $9.36 million" (Martz and Carroll, 63). While it is not uncommon for evangelists, especially those who minister via television, to ask for donations from their congregants and viewers, the Bakkers presented a unique example of the misuse of such funds through their extreme extravagance. Lavish spending included, ". . .a flight to Europe on the Concorde, with seats at more than $2,000 apiece. . .an $800 briefcase; a $70 address book; a $74 toilet kit from Gucci; a $120 pen. . ." (Martz and Carroll, 65). It was clear that the Bakkers had been misusing funds; ". . .an IRS worksheet [stated] that Jim Bakker had taken undocumented expenses totaling $860,000 in 1985" (Martz and Carroll, 165). Because of their extravagance and Jim's alleged sexual misconduct, the Assembly of God denomination defrocked the Bakkers, and Jerry Falwell, an evangelist from Lynchburg, Virginia, took over the PTL network that later folded completely. Most agree that Falwell's actions in the proceedings were more aligned to the advancement of his own career than Christian compassion for a fellow minister. This may be most evident in Doug Marlette's editorial cartoon that appeared in the Charlotte Observer. In his depiction, Falwell is portrayed as the Edenic serpent, greedily wrapping himself around the PTL empire, while publicly presenting himself as the Bakkers' saving grace. However, despite the greed exhibited on Falwell's part and the evidence that evangelists often fall prey to vices, the avarice exhibited by the Bakkers was unprecedented, and remains one of the best illustrations of the misuse of congregants' trust and donations.

Sex

Greed is not the only motivating factor in the evangelical movement, however. Just as in camp-meetings, modern evangelists often fall prey to the temptations of lust, many in the public eye. Jim Bakker fell to the temptation of lust and was accused of adultery. It was because of this adultery, not because of his misuse of funds, that Bakker was removed from ministry. Although the financial situation was what caused Bakker to be watched, it was the adulterous action that created the ultimate downfall. While one's congregants often accept greed, sex becomes more problematic within the realm of the Church. Randall Balmer notes that "Some commentators made much of the fact that Hahn (after the requisite plastic surgery) [Jim Bakker's secretary with whom he had an alleged affair] appeared in Playboy, while the woman linked with [Jimmy] Swaggart appeared in Penthouse" (35). In the modern era in which sexuality is already a burgeoning market, it is clear that these showmen of the Church are unable to resist its lure. Unlike the sexual undertones of the camp-meeting preachers' revivalist techniques, modern day evangelists' sexual misconduct is much more blatant, undercutting their credibility as 'men of God' and proving their ultimate humanity.

One of the best modern examples is that of Jimmy Swaggert. Swaggert, whose cousin was Jerry Lee Lewis, came from a long line of showmen, building an empire on his televangelism. Ironically, after criticizing the sexual misconduct of other ministers such as Jim Bakker and Marvin Gorman, Swaggert was filmed entering a Louisiana hotel room with a prostitute. Before his own transgressions were uncovered, Swaggert had stated in his magazineThe Evangelist, "To allow a preacher of the Gospel, when he is caught beyond the shadow of a doubt committing an immoral act . . . to remain in his position as pastor (or whatever), would be the most gross stupidity." (Ostling, 55). However, after the Assemblies of God denomination suspended him from preaching for two years, Swaggert defied the decision and went back to his ministry after three months (Balmer, 34). Again, the theological stance once adopted by a hard-line evangelical had to be bent in order to maintain a position of religious leadership and power.

From a literary perspective this sexual misconduct is rampant in Sinclair Lewis' Elmer Gantry. As a minister Elmer is expected to be a mainstay of moral society. However, this is clearly not the case as Lewis writes, "He [Elmer] had, in fact, got everything from the church and Sunday School, except, perhaps, any longing whatever for decency and kindness and reason" (28). It is clear from early on in the novel that one of Elmer's greatest flaws is his inability to curb his womanizing tendencies. Lewis writes of Elmer's lust, "Lulu Bains had been a tempting mouthful; Cleo Benham was of the race of queens. To possess her, Elmer gloated, would in itself by an empire, worth any battling yet he did not itch to get her in a corner and buss her, as he had Lulu. . ." (268). Caught between his love of money and his love of sex, perhaps the two strongest temptations for evangelists, Elmer chooses to marry Cleo for her money and carry on extramarital affairs to assuage his lust. Lewis writes, "He kept himself from paying any attention, except rollickingly kissing her once or twice, to the fourteen-year-old daughter of his landlady. He was, in fact, full of good works and clerical exemplaries" (288). Elmer's duties as a minister keep the temptations of sex at a distance, yet do not erase them. In the end of the novel, Elmer has become an established evangelist. However, his womanizing has not yet ended. During a prayer "[h]e turned to include the choir, and for the first time he saw that there was a new singer, a girl with charming ankles and lively eyes, with whom he would certainly have to become well acquainted. But the thought was so swift that it did not interrupt the paean of his prayer. . ." (Lewis, 432). Lewis' satirical view of evangelism's dualities is clearly illustrated through Elmer. Even as he prays to make America a moral nation, Elmer habitually falls prey to his own immoral temptations. Literarily, Lewis has portrayed the hypocritical stance an evangelist who has not lived up to his call must assume. To maintain religious leadership Elmer Gantry must preserve the façade of piety, while his baser human lusts lead him to undercut that piety through sex and greed.

Violence

Just as in camp-meetings, preachers today often struggle with the temptation to abuse the power invested in them by their congregants. This may take the form of greed or sex, but it is also played out through brutality and violence. While preaching divine traits such as peace and love, as humans, these preachers often fall short. One of the most vivid portrayals of this brutality is in the movie "The Apostle." Robert Duvall, as Sonny, a Pentecostal Southern evangelical preacher, is unable to control his abusive use of power. An adulterer himself, Sonny is unable to handle his wife's infidelity. After she leaves him, he confronts her lover at a baseball game. Drunk and angry, Sonny swings a baseball bat at the man's head, knocking him to the ground. This abuse of power plagues Sonny through the rest of the movie. Eventually, he finds that this outburst of violence has eventuated the man's death. Charged with murder, Sonny is taken to jail to face the consequences of his actions. As he is taken to jail he tells a recently converted member of his congregation, "You're going to Heaven. I'm going to jail and you're going to heaven" ("The Apostle"). In the end, Sonny's misuse of physical power brings about his downfall. However, "The Apostle" may be viewed as a tale of redemption. It is through Sonny's loss of the power over his wealthy church, his loss of family and roots, and his misuse of power that Sonny is forced to reclaim his faith. Although his sins are not forgotten, and are punished by society, it is through the consequences of his brutality and violence that Sonny is actually redeemed and reconciled with his faith.

In another example of a preacher's use of violence, the film "The Night of the Hunter" traces the story of Reverend Harry Powell, played by Robert Mitchum, as he is released from jail only to murder for wealth. In one scene the preacher summarizes the dualities of love and hate that exist within many preachers in his explanation of the tattooed words across his knuckles. Although Reverend Powell exhibits this polarity to a much more deadly extent than many modern evangelists, his explanation of the dichotomy is quite instructive. After noticing John's interest in the words 'love' and 'hate' that are tattooed across his knuckles, the preacher explains:

Ah, little lad, you're staring at my fingers. Would you like me to tell you the little story of right-hand/left-hand? The story of good and evil? H-A-T-E! It was with this left hand that old brother Cain struck the blow that laid his brother low. L-O-V-E! You see these fingers, dear hearts? These fingers has veins that run straight to the soul of man. The right hand, friends, the hand of love. Now watch, and I'll show you the story of life. Those fingers, dear hearts, is always a-warring and a-tugging, one agin t'other. Now watch 'em! Old brother left hand, left hand he's a fighting, and it looks like love's a goner. But wait a minute! Hot dog, love's a winning! Yessirree! It's love that's won, and old left hand hate is down for the count! ("The Night of the Hunter").

"It is obvious in the preacher's explanation of this struggle between good and evil that exists within him, that each preacher fights a constant battle between the demands of his calling and the standards set by his faith and the reality of his own humanity and sinfulness.

The brutality that is exhibited in "The Apostle" and "The Night of the Hunter" is also evidenced in real accounts of modern evangelists. Whereas in "The Apostle" brutality that goes unchecked is punished, often in the realm of real evangelists brutality is overlooked. Instead of taking part in the abuse themselves, evangelists demand the allegiance of their workers to be proven through their physical overpowering of their critics. While in "The Apostle" it is the minister himself who is unable to control his temper, in the case of A.A. Adams, the preacher stayed outside of the ring of violence, yet allowed his followers to implement it in order to uphold his reputation. After Adams was arrested for drunk driving, Morris writes of a reporter for the Knoxville Journal being "thrown out of the services when some of Allen's men noticed he was taking notes. Webb [the reporter] later revealed that outside the tent his escorts had slugged him twice on the head and warned him: 'Don't ever come back'" (15). It is through violence, therefore, that many evangelists like Adams ensure that their reputations are not soiled. While during camp-meeting times the preacher himself was often accused of brutality, within the modern evangelical movement this brutality has often been relegated as a job for the preacher's men, further removing the preacher from any personal blame. However, the legacy of brutality remains.

Entering the Politics Game

The power that preachers exert over their congregants is not always physical, however. Often, more dire is the mental and emotional power that the modern evangelist can hold over his followers. This is most clearly evidenced in many modern televangelists' involvement in political parties and politics in general. The lure of the political arena is described by Perry Deane Young who writes, ". . .the preachers have always known where the money was, and from the first settlements they have by and large aligned themselves with the wealthy and powerful" (162). These wealthy and powerful most often reside, according to Young, within the political field. Jeffrey K. Hadden and Charles E. Swann note, ". . .the new ingredient in the emerging coalition is the belief that it is the responsibility, indeed the duty of Christians to engage in the political process as a means of bringing America back to God. . .they believe morality can be legislated. Therefore, it is important to get the right people elected to office" (134). One of the best illustrations of modern evangelism's power is that illustrated within the political arena. As demonstrated by James Robison, a leader of one of the New Christian Right's groups, evangelism has distinct power over the election of state and federal officials. This move to involve Christians in the political affairs of America has been spearheaded recently by the conservative Christian evangelists, of whom the modern evangelist preacher is often the leader.

As the evangelists have gained power in their own right, as illustrated through their ability to procure huge amounts of money, politicians have taken note. Now, within this modern era, conservative Christians have aligned themselves with conservative politicians to create a symbiotic relationship that increases both groups' impacts. Hadden and Swann note:

The New Right sought to recruit television preachers for some time before it succeeded. . .They frequently invoke the name of God as the progenitor of their cause, but they need highly visible religious leaders to sanctify the invocations. . .The New Christian Right, thus, obviously owes its genesis to the master plan of the New Right. . .The technology that the New Right is using to transform American politics is essentially the same technology that the televangelists are using to build their religious empires (142-143).

"It is out of this mutually beneficial relationship between the highly visible Christian evangelists and the politically savvy conservative politicians that groups such as the Moral Majority have originated.

As one of the evangelists most involved in the public arena, fundamentalist Jerry Falwell entered the political field through his involvement in the establishment of the Moral Majority. The Moral Majority, a conservative Christian political organization, utilized Falwell's position as a church leader to claim God as political backer. His involvement caused a large amount of controversy, as his highly conservative ideals were foreign to many more liberal Christians who did not like being aligned with the Moral Majority in the political arena. Of Falwell's involvement in the Moral Majority, Young writes, "I think the political pros wanted Jerry Falwell precisely because he had none of these qualities [showmanship, good-looks, charisma and intelligence, according to Young]. He had no publicly identifiable politics, so they could mold him as they saw fit; he could head up their new coalition of single issues because he hadn't spoken out on any of them. . ." (197). For evangelical Christians, Falwell represented a new move to infuse 'morality' into an ethically dead political realm. In an interview Falwell stated, "Church people. . .are the secret ingredient that none of the pollsters counted on" (Hadden and Swann, 161). In a photograph of a rally of Christian Right voters, Falwell stands in front of a line of American flags, clearly illustrating the alignment of church and state within the ideologies of groups such as the Moral Majority. On June 11, 1989 the Moral Majority folded due in part to the negative light on which the indictments of Bakker and Swaggert cast evangelism in general. However, the religious right remains intact and powerful (Institute for First Amendment Studies). This realm of church and state's intermingling has added a new dimension of power for the evangelical preachers. Now, not only are their voices heard from the pulpit, but they are also heard from the lecterns of political rallies.Conclusion

Therefore, it seems clear that preachers from camp meetings to the modern evangelists, are often swayed by the lure of power to the point of perverting the holiness of their callings. Although the dualities that were present in the camp-meeting preachers are echoed in these modern evangelists, the manner by which the modern preacher acts on this struggle between right and wrong is sometimes different from the camp meeting preacher. This may be explained through the difference in the preachers' environments. While camp meeting preachers were often quite blatantly violently in order to survive their frontier surroundings, modern evangelists utilize violence only through others in order to retain their reputations. On the other hand, while camp-meeting preachers were often sexual in the undertones of their ministries, it was rare that they ever acted on these lustful desires. However, in the modern era as sexuality has become more readily accepted by the general public, evangelists are often accused of blatant sexual misconduct. Therefore, while dualities still exist in modern evangelists, the tenor of these dualities has shifted as the society to which they minister has shifted ideologically and in its principles.

Within the social and religious spheres of the camp meeting there was a constant division between the co-existing elements of good and evil. Both literary and historical accounts of camp meeting preachers illustrate the ways in which he embodied piety and sinfulness, humility and power. As one of the most pivotal leaders of the religious sphere both in frontier and modern times, preachers utilized their power in order to influence their congregations. While some ministers rejected the power they were given through their esteemed position, others reveled in it. In order to maintain their power, ministers often adopted the rough-and-tumble habits of their congregants, in the process sacrificing the theology of equality that their evangelical background led them to espouse. Likewise in modern times, evangelists wield hefty amounts of power both politically and spiritually over their congregants in order to procure wealth, sex and prestige. Often their theology must shift in order to accommodate their newfound power and wealth. These elements of power, sex and money are hopelessly tangled, creating a strange conglomeration of sins that merges with the pious aspects of these ministers. It is through this strange melding of the elements of virtue and vice that preachers evolve and appear as some of the most interesting and entertaining figures, both in the frontier and in modern America.

Works Cited

Anonymous. "The Harp of a Thousand Strings: A Hard-Shell Baptist Sermon." Free-Thought on the American Frontier. Ed. Fred and Verle Muhrer Whitehead. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1992. 56-60).

Balmer, Randall. "Still Wrestling with the Devil: A Visit with Jimmy Swaggert Ten Years After His Fall." Christianity Today 2, March 1998: 31-38.

Boles, John B. The Great Revival: Beginnings of the Bible Belt. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1972.

Bruce, Dickson D., Jr. And They All Sang Hallelujah: Plain-Fold Camp-Meeting Religion, 1800-1845. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1974.

Douglas, Marian. "Before the Wedding." The Atlantic Monthly [Boston] December 1872: 685-87.

Duvall, Robert, dir. The Apostle. Rec. 1997. Butchers Run Films, 1997.

Ellsworth, Rev. W. I. "Reminiscences of a Camp Meeting." The Ladies' Repository [Cincinnati] November 1848: 341-43.

Gardner, H.C. "Going to Camp Meeting." The Ladies' Repository [Cincinnati] November 1863: 644-49.

Grafton, Mary E. "A Story of the Camp-Meeting." Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine [San Francisco] May 1886: 497-504.

Hadden, Jeffrey K. and Charles E. Swann. Prime Time Preachers: The Rising Power of Televangelism. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc., 1981.

Harris, George Washington. "Parson John Bullen's Lizards." Humor of the Old Southwest. 3rd Ed. Ed. Hennig and William B. Dillingham Cohen. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1994. 206-12.

Hatch, Nathan O. The Democratization of American Christianity. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Heyrman, Christine Leigh. Southern Cross: The Beginnings of the Bible Belt. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997.

Hines, Rev. Gustavus. "The Camp Meeting: A Reminiscence"." The Ladies' Repository [Cincinnati] June 1853: 259-61.

Hooper, Johnson Jones. "The Captain Attends a Camp Meeting." Humor of the Old Southwest. 3rd Ed. Ed. Hennig and William B. Dillingham Cohen. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1994. 291-99.

Laughton, Charles, dir. The Night of the Hunter. Rec. 1955. United Artists, 1955. 93 minutes.

Lewis, Sinclair. Elmer Gantry. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1927.

Loveland, Anne C. Southern Evangelicals and the Social Order: 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Lousiana State University Press, 1980.

Lorenzo Dow and the Jerking Exercise. Engraving by Lossing-Barrett, from Samuel G.Goodrich, Recollections of a Lifetime. Copyprint. New York: 1856 General Collections, Library of Congress (195).

Marlett, Doug. "Editorial Cartoon." Ministry of Greed: The Inside Story of the Televangelists and Their Holy Wars. Larry Martz and Ginny Carroll. New York: A Newsweek Book, 1988.

Martz, Larry and Ginny Carroll. Ministry of Greed: The Inside Story of the Televangelists and Their Holy Wars. New York: A Newsweek Book, 1988.

Mondy, Robert William. Pioneers and Preachers: Stories of the Old Frontier. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1980.

"Moral Majority Folds." Institute for First Amendment Studies, Inc: Freedom Writer June/July/August 1989. http://www.ifas.org/fw/8906/majority.html (20, April, 2001).

Morris, James. The Preachers. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1973.

Ostling, Richard N. "Worhipers on a Holy Roll: Scandals and Swaggart Fail to Deter." Time 11, April 1988: 55.

Rider, Alexander. "Camp Meeting." Early 19th century.

Taliaferro, Hardin E. "Parson Squint: By Skitt, Who Has Seen Him." Humor of the Old Southwest. 3rd Ed. Ed. Hennig and William B. Dillingham Cohen. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1994. 143-47.

Waud, A.R. "The Circuit Preacher." Engraving of the Drawing. Harper's Weekly.

Young, Perry Deane. God's Bullies: Native Refelctions on Preachers and Politics. NY: Holt, Rienhart & Winston, 1982.

Notes:

Kristin Adkins Whitesides graduated magna cum laude from the University of Richmond in 2002 with a bachelor of arts in religion and English. She is currently in her senior year at Duke Divinity School where she is pursuing an M.Div [master of Divinity] degree. At Duke Kristin has concentrated on Old Testament studies and American religious history. Her particular interests include women’s roles in theology and ministry, Baptist history and heritage, Jewish-Christian relationships, Biblical exegesis, and the separation of church and state. She hopes to pursue ordained ministry after graduation, although she may find the lure of further graduate study too hard to resist.

| We would like to thank the staff of the Library of Virginia Archives and Special Collections, Alderman Library, and Barrett Collection for their assistance. This page contains material in the public domain and it may be reproduced in its entirety or cited for courses, scholarship, or other non-commercial uses. We ask that users cite the source and support the archives that have provided materials to the Spirit site. |